An $8 Million Man?

Connecticut Law Tribune

March 19, 2012, page 1

Exonerated inmate using new statute to pursue compensation

By THOMAS B. SCHEFFEY

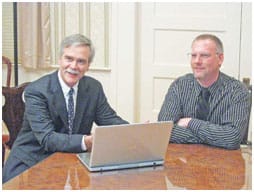

Kenneth Ireland (right) and his attorney, Wiliam Bloss, will take their wrongful imprisonment claim for $8 million to a hearing before the state claims commissioner.

Before Connecticut had a statute spelling out how wrongful imprisonment claims were to be pursued, James Tillman was aided by pro bono lawyers who lobbied the legislature to provide $5 million in compensation.

The U.S. is a crazy quilt of disparity when it comes to compensating prisoners for wrongful imprisonment, and Connecticut, too, has been all over the map.

In 2007, James C. Tillman was offered $500,000 by then-Gov. M. Jodi Rell to help make up for the 18 years he spent in prison for a rape he did not commit. A year later a group of pro bono lawyers lobbied for a special legislative act that eventually paid Tillman $5 million.

After that, the legislature in 2008 passed a law that created a formal method – involving the state claims commissioner – for winning compensation for wrongful incarceration. It just so happened that one Connecticut man was freed that year – Kenneth Ireland.

The Connecticut Innocence Project, headed by attorney Karen Goodrow, used modern DNA evidence testing to free Ireland after he had spent 21 years in Connecticut and Virginia prisons for allegedly killing a factory worker in Wallingford.

Now another pro bono lawyer, William C. Bloss of Bridgeport’s Koskoff, Koskoff & Bieder, is shepherding Ireland through the first claim under the new law, with a request for $8 million.

“Like any serious case, where there are serious injuries or wrongful death, the calculation of damages is an imperfect science,” Bloss said. “We leave a great deal of discretion to the fact finder to try to make a rough comparison between compensatory damages and the wrong that has taken place. Twenty-one years of confinement, 21 years of lost liberty for an offense he simply did not commit, is … plainly significant.”

The New York office of the National Innocence Project says 27 states have compensation laws. Some award released inmates only $2,000 for each year of wrongful imprisonment. The top payer is Texas, which provides $90,000 per year of wrongful imprisonment.

Some states are in-between: Under Virginia’s formula, a wrongfully convicted person can receive 90 percent of the state’s average per capita personal income for each year of incarceration. That works out to roughly $40,000 a year for each year in prison, but it’s capped at 20 years, making the maximum payout about $800,000.

“A lot of states have a long way to go,” said spokesman Paul Cates.

In places with no formal compensation laws, exonerated inmates often end up suing state officials and law enforcement authorities in federal court. In 2010, a Manhattan jury ended up awarding $18.6 million to a Bronx man who had been wrongly imprisoned on a rape charge for 20 years. Earlier this year, a 32-year-old Chicago area man who had been exonerated after serving 16 years on a murder charge, was awarded $25 million by a federal jury in Illinois.

‘Loss Of Reputation’

Attorney Bloss said the new statute, Connecticut General Statutes Sec. 54-102uu, has very clear terms. At a hearing, the exonerated inmate can argue for damages to cover loss of liberty and enjoyment of life, “loss of earnings, loss of earning capacity, loss of familial relationships, loss of reputation, physical pain and suffering, mental pain and suffering” and the costs of criminal defense.

Bloss said the claims commissioner (whose main job is to determine who can sue the state) also is required to consider whether any negligence or misconduct by the state contributed to the arrest, prosecution, conviction and incarceration. “The evidence in [Ireland’s] case was very slim – no physical evidence whatsoever, connecting him to the offense,” said Bloss.

Ireland was 18 and living in Manchester when he was arrested for the 1986 rape and beating death of Wallingford factory worker Barbara Pelkey, 30. She was working alone, overnight, as a $5-an-hour fiberglass chair weaver at the R.S. Moulding and Manufacturing Co., located in an industrial park. Last year, the DNA evidence that freed Ireland led to the conviction of another man.

“Ken has concerns about the initial investigation which are reasonably well-founded,” Bloss said. “But at least the police did not discard the evidence after the convictions. If they had, the DNA couldn’t be tested and Ken would have to die of old age in prison.”

Ireland says at times all hope seemed lost. “The police initially tried to test the DNA, while I was going to trial, back in 1989 and 1990. The [right] technology didn’t exist then. The results came back inconclusive, ‘not enough sample to test.'”

Even worse, there was a notation on the bottom of the page: “sample consumed during testing.”

“Then in 1994, through a habeas attorney, I tried to have it tested again, but the technology still wasn’t up to par,” Ireland recalled. Still, he didn’t give up.

“So by the time the Connecticut Innocence Project notified me that they were about to send it out again, I asked, ‘Are we sure the technology had caught up now?’ They were sure the technology had caught up.” But finding enough remaining DNA sample to test was a huge barrier.

“Reading through my transcripts, I was noticing how the medical examiner was explaining how they examined the evidence. They took a Q-tip smear on a glass slide, and put it under a microscope. All of a sudden, a once-in-a-lifetime light bulb moment it hit me…. Where is this glass slide? And they were able to find the slide, in some locker somewhere.”

And that was the beginning of the Ireland’s route to freedom.

He currently works in the business services department of CREC, the Capitol Region Education Council in downtown Hartford, “crunching numbers,” as he puts it.

Earnings Potential

An economist will help present the case of Ireland’s lost earnings.

Ireland says it’s hard to guess how his life would have turned out without the arrest and conviction. He was 18, had just finished his Graduate Equivalency Degree, and was preparing to ship off to Ft. Benning, Ga., for basic training in the National Guard.

“I got arrested before I went. I basically joined just to get the college money,” he said. “My potential at that point, you couldn’t really chart it. I hadn’t begun yet…If an economist comes in to try to measure potential lost earnings, how do you measure something like that? My potential was limitless at that point.”

As for non-economic damages provided in the state statute – including the physical and mental pain and suffering – Ireland thinks he has a good case. While he took advantage of a wide range of education programs while incarcerated, including college correspondence courses, he called prison a “horrible, crazy” place. Ireland said that especially describes the five years he spent in a facility in rural, western Virginia under a now-defunct program that sent Connecticut inmates out of state to alleviate in-state prison crowding.

“It was absolutely nightmarish,” he said. “Any kind of stepping out of line, and [correction guards] would fire a shotgun inside the unit. “The first shot is a blank round. But inside a concrete block, it’s deafening. Everybody has to lie on the floor, or if outside, in the snow or water or wherever you are.”

Ireland continued: “If they go to a second round, it’s an actual live round of plastic pellets that embed themselves in your skin. You’re then taken to [a medical unit] afterwards, and they have to pluck these from your flesh. “

Ireland said two inmates from Connecticut actually died there under questionable circumstances, and that he was later transferred to a much more pleasant prison on the eastern side of Virginia.

Surprisingly, Ireland does not speak with bitterness. He sounds genuinely pleased by the formality and apparent even-handedness of Connecticut’s new compensation system.

“There are states out there where you don’t get anything. You don’t get a pat on the back, a ‘we’re sorry.’ You’re on your way to make the best you can of life,” he said. “People have been released with no job skills, no education, and they’re out on their own and don’t know anything about how to survive in the real world.

“We’re really actually lucky that Connecticut has a statute,” Ireland concluded. “It hasn’t been tried yet, so we’re breaking new ground.”